SRINAGAR, India — Holding two finely crafted wooden mallets between his index and middle fingers, Ustad Mohammad Yaqoob Sheikh strikes his santoor, a hundred-stringed instrument from the majority-Muslim Kashmir Valley.

The metallic “ting” notes overlap to create a choral ensemble, performed with rapid fluidity atop carpets while Sheikh sits cross-legged.

In the fading sunset, the music gives Sheikh’s home a mystical quality among the many other houses tightly clustered along narrow alleyways in Old Srinagar.

“We perform this music only when light fades and dusk approaches,” said Sheikh, a maestro of Kashmiri classical music called Sufiana Mausiqi (meaning mystical music). The art form is distinctly peaceful and religious, drawing lyrics from Sufi poets of the mystical Muslim tradition and performed in both Sufi religious and secular gatherings.

Sheikh’s mastery over 62 such modes in Persian, Urdu, Punjabi and Kashmiri makes him an exception in the changing socio-economic fabric of Kashmir.

Only a few traditional practitioners of Sufiana Mausiqi remain in Kashmir. They perform compositions by Sufi mystics such as Jalaluddin Rumi, Omar Khayam, Amir Khusro and Hafiz. Their distinctive musical lineage and ideology is now facing threats of extinction.

Political instability, government apathy and decades of conflict have relegated it to the margins, along with a growing popularity of folk, light Indian classical and Bollywood music.

Kashmir has been at the heart of the territorial conflict between India and Pakistan, which emerged as sovereign states after the overthrow of British rule in 1947.

The Indian government’s drive against separatist militants in Kashmir Valley is marked by large-scale human rights violations—including shooting of unarmed demonstrators, enforced disappearances and killings, according to the UN.

The tensions in the region have marginalized the rich cultural legacy of Kashmir with Sufiana Mausiqi as one of its bulwarks.

“Sufiana music has suffered due to the tense political climate here. Its deep spiritual roots should have been harnessed to propagate peace,” Sheikh said.

According to Sheikh, the music’s transcendental power helps listeners discern the illusory world around them and reach a higher state of consciousness.

Mohammad Yusuf Taing, a reputed scholar and critic based in Srinagar, notes, “Sufiana music is full of love, fraternity and brotherhood. It’s the fountain of our soulful music.”

Should the Indian government revive Kashmiri classical music?

Both its practitioners and listeners believe an immediate rescue effort by the government is needed to revive Kashmiri classical, a centuries-old tradition that shaped the region’s unique identity as the cradle of Sufism in South Asia.

This tradition is believed to have come from Persia sometime in the fourteenth century and grew as a product of cultural intermingling in the Kashmir Valley.

The maestros who inherited the legacy from their forefathers—an elite class of masters such as Muhammad Abdullah Tibetbaqal, Ghulam Muhammad Qaleenbaaf, Abdullah Shah and Ramzan Joo, made it the crucible of many art forms in the Valley.

While nobles and barons patronized this art form, traveling Sufi mystics who preached peace, tolerance, pluralism and universalism infused it with a deep spirituality.

The nobility even brought their progeny to the Sufiana ensembles to teach them etiquette and decency through the lens of fine art.

“Even though many of Kashmir’s maharajas were Hindu by faith, they could read and write in fluent Persian. They took a special interest in this musical tradition,” says Zareef Ahmad Zareef, a Kashmiri writer and social activist.

But with the end of imperial rule in Kashmir in 1947, Sufiana music was stripped of its royal patronage. It became merely a performance art in the homes of the Muslim nobility and at Sufi shrines.

Even then, its appeal to morality, religion, romanticism and poetry did not wear off.

After India’s independence from colonial rule, the government-run All India Radio tried to promote Sufiana music, but its efforts have been limited due to lack of funds. And the current Hindu nationalist government under Prime Minister Narendra Modi is more concerned with promoting India’s Hindu heritage than minority religions, seen by the far-right as foreign religions.

Initiatives by other cash-strapped government-run organizations such as the Jammu and Kashmir Cultural Academy and Doordarshan, an Indian broadcasting network, have been few and far between.

“The government has obliterated the cultural legacy of Kashmir in the name of security and counter-terrorism,” said Gulzar Ahmad Ganai, an award-winning Kashmiri folk singer, who feels let down by the politicians.

Ganai notes that the disenchantment of musicians has grown since the unrest following the killing of Burhan Muzaffar Wani, the late commander of the Kashmiri militant group Hizbul Mujahideen gunned down by Indian security forces in 2016.

“Allah knows how we survived six months of curfew and crackdown on civilians,” Ganai said. “Only the spiritual strength of our music kept us going.”

Dwindling numbers of students, especially girls

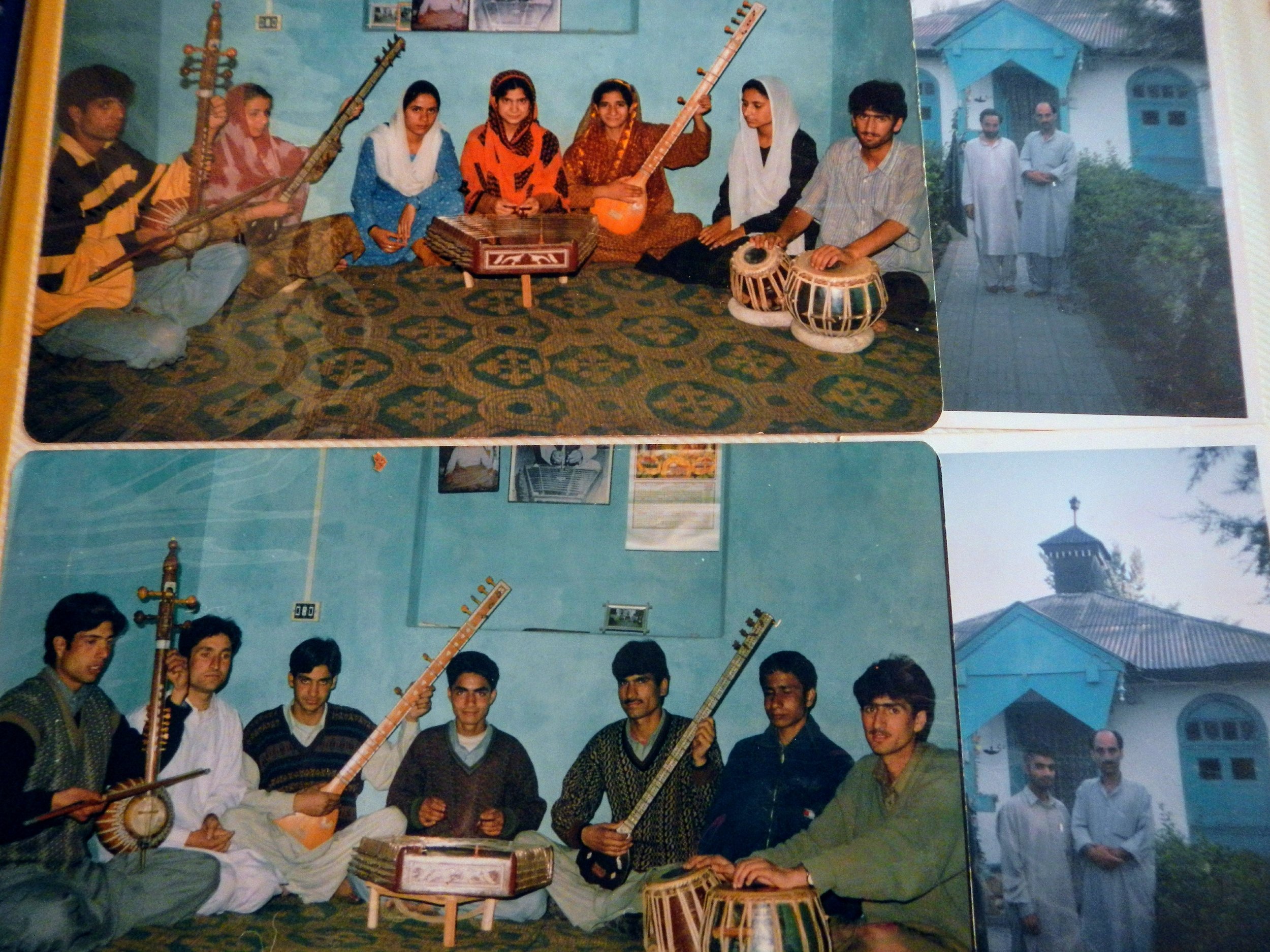

Despite crackdown by the security forces, Sheikh continued to train his students whose numbers have now dwindled to 35—a smattering in Kashmir’s fertile creative landscape.

“It’s not easy to safeguard this tradition when you have no support, and face opposition from orthodox clerics or militants who demand to know what you are up to,” he said.

When Sheikh started teaching girls in 1998, there were more than 21 girls in his classes. Now, only eight are left.

Shubeena Akhtar, one of his students, says women need more support in a traditional society where social pressures and orthodoxy limit their exposure to the arts.

An all-girl band in Kashmir was forced to disband after their concert in 2013 when a top Muslim cleric issued a fatwa ordering the girls to “stop these activities and not get influenced by political leadership.”

“We need scholarships and institutions, otherwise girls who have the aptitude for music will simply be married off or silenced,” Akhtar said. “Our tradition will die.”

Sheikh believes he is the only practitioner to champion gender equality in musical learning, just like his grandfather Ghulam Mohammad Qaleenbaf, a legendary Sufiana musician bred in one of Kashmir’s reputed carpet-weaving families in the early twentieth century.

The maestro has built a separate hall in his house where students can practice for as long as they want. They don’t need to buy instruments or pay for their tuition.

“These instruments can cost above $300, and many students from poor families can’t afford to pay,” he said. “So, I train them for free if they’re diligent.”

Many traditional instrument-making families have died out in Kashmir due to lack of government support. But traditional families like Sheikh’s are fueled by their forefathers’ zeal to keep this tradition alive above material gains.

Mushtaq Saaznawaz from one of the most renowned schools of Kashmiri classical music, says he provides free training, research materials and food to his students to prevent their exodus to more lucrative areas of work.

“But this isn’t enough,” Saaznawaz said. “It takes around 25 years for any student to reach a level of proficiency in classical music. We need a proper Sufiana music institute, scholarships and global recognition.”

Another challenge is that Jammu and Kashmir often tops Indian states for unemployment, measured at 25 percent of the working population unemployed in 2017 versus 13 percent nationally. Youth are particularly affected by joblessness and preoccupied searching for ways to make income rather than music.

With Sheikh set to retire, there’s no one to fill his place yet

Radio Kashmir, which is controlled from Delhi, has de-prioritized Sufiana Mausiqi, and Sheikh is their only permanent staff member currently.

“Since 1992, no recruitments have taken place and 23 positions for musicians are lying vacant in the Srinagar office,” said Nawaz Ahmed, the program head of Radio Kashmir.

When Sheikh retires next year, the space for Kashmiri classical music may shrink further.

In contrast, folk and classical musicians receive ample patronage from the government at All India Radio’s well-appointed office in Delhi.

“Currently, we have 20 staff musicians and 700 empaneled artists who are roped in when required,” says Veena Pahari, an assistant director of programs at All India Radio’s Delhi office.

Some attribute Kashmiri classical music’s decline to lack of flexibility and innovation by the maestros, and the urge to maintain written records of their notations.

“We can’t squarely blame the government,” said Mohammad Ashraf Tak, a chief Urdu editor at the Jammu and Kashmir Cultural Academy in Srinagar.

“The traditional families are reluctant to share their musicological ideologies, forms and styles, so outsiders are rarely entertained,” he said. “But things are changing now.”

Amid all the finger-pointing, there’s a sense that the government approach to cultural preservation needs to be seriously examined and the essence of Kashmiri classical music reinstated.

“Our music has always risen above conflict and discrimination on the basis of religion,” Sheikh said. “If we revive it, it will water the spiritual heart of Kashmir and the world.”

Priyadarshini Sen is an independent journalist based in New Delhi. Originally written for Religion Unplugged.