(for Yonnas)

If you’re anything like me, you’re black.

But what does that mean?

We deal in too many externals, brother

Always Afros, handshakes and dashikis

As I walk in, there are four people on stage. Or is it a stage? It must be because I have come into a space I know to be a theater. But it’s not a proscenium or a thrust. The architecture of the space as I currently view it is not so much naturalistic as hypernaturalistic. It looks exactly like a cluttered rehearsal room, which, I expect, it is. Off to my left are a couple of couches, a door that leads outside, shelves, water bottles, boxes, detritus. The flotsam of theater. A fifth actor is milling about while the other four do stretching exercises. I sit down and begin to concentrate on my breathing. I want to be calm. I want these people to show me what they’ve got.

A black play is told that it is about race and a black play knows it’s really about other shit.

A black play knows that racerelations sell.

A black play knows that racerelations are a holding cell.

To many, I’m not black enough. Even if I pass the brown paper bag test, as I’m known to do during soccer season, I will never fit comfortably among that blacker-than-thou faction of African Americans who seem to believe they hold the silver keys to the Pearly Gated Community of Blackness. (Playing soccer itself rules me out of that hallowed ground, since, as I’ve been told hundreds of times in my life, black people don’t play soccer.)

A black play does not exist.

Every play is a black play.

SAY WHAT?

I’m thinking about Langston Hughes, Malcolm X, George C. Wolfe. I’m wondering what I know about colonialism. I have a bunch of thoughts buzzing through my head, each of them inadequate, insufficient. I breathe more slowly.

You see, unfortunately, I am not black. There are lots of different kinds of blood in our family. But here in the United States, the word “Negro” is used to mean anyone who has any Negro blood at all in his veins. In Africa, the word is more pure. It means all Negro, therefore black. I am brown.

A sixth actor scrambles onto the stage into the playing area where a fairly short, brown-skinned actress introduces herself as introducing others who play the parts of themselves plus the parts they play as they play before us. That sounds right. I recognize instantly that I’m in the land of Brecht, that playwright whom Americans allegedly dislike.

They may or may not dislike him. What is more certain is that they’ve probably never seen him. Much of this is down to translation. John Willett’s Brecht on Theatre, which is generally all Americans know about Brecht’s theoretical writing features a five page essay “On Experimental Theatre.” The footnote reads that it is translated from “Über experimentelles Theater” and taken from Schriften zum Theater pg. 79-106. No one I know has ever questioned how twenty-seven pages could be reduced to five. No one I know has expressed frustration with the fact that Brecht’s Über experimentelles Theater is actually a 168-page book. They simply read five pages and think they’ve grasped all they need to know.

Was konnte an die Stelle von Furcht und Mitleid gesetzt werden, des klassischen Zwiegespanns zur Herbeiführung der aristotelischen Katharsis? Wenn man auf die Hypnose verzichtete, an was konnte man appellieren? Welche Haltung sollte der Zuhörer einnehmen in den neuen Theatern, wenn ihm die traumbefangene, passive, in das Schicksal ergebene Haltung verwehrt wurde? Er sollte nicht mehr aus seiner Welt in die Welt der Kunst entführt, nicht mehr gekidnappt werden; im Gegenteil sollte er in seine reale Welt eingeführt werden, mit wachen Sinnen. War es möglich, etwa anstelle der Furcht vor dem Schicksal die Wissensbegierde zu setzen, anstelle des Mitleids die Hilfsbereitschaft?

To others, all us darkeys look the same. And even if I cut my hair and enjoy my umpteenth long, overcast Seattle winter, I will certainly never fit unnoticed among white folks. On either side of the gates, I will always be viewed with circumspection.

…my beautiful black brothers and sisters! And when we say “black,” we mean everything not white, brothers and sisters! Because look at your skins! We’re all black to the white man, but we’re a thousand and one different colors. Turn around, look at each other!

And so I looked forward to Pony World’s presentation of We Are Proud to Present a Presentation about the Herero of Namibia, Formerly Known as Southwest Africa, from the German Sudwestafrika, Between the Years 1884-1915 so successful? Why do I love the script so much? Why do I love the conception by director David Gassner and his crew? Why is it so incredibly effective in this interpretation?

It’s not naturalistic.

It doesn’t demand emotion. It demands thought. Emotion comes along as a matter of course.

It is against catharsis.

So I started doing research about the genocide. Then I went to graduate school, and was sitting on this stack of information, and tried to write a play about the Herero Genocide as my graduate student thesis.

That play was really terrible. Yay, terrible plays. I had a reading of it in the middle of the semester. And I was like, “oh no, how am I going to graduate? I need that paper that tells me I’m allowed to be a playwright. Oh, no!”

I freaked out. Got more and more interested in the ways in which I felt the play was failing.

I introduced this meta-theatrical element (the big M-word) that allowed a group of actors to struggle with a similar thing that I felt I was struggling with – in trying to capture in this story.

Meta-theatrical. Fancy way of invoking the Verfremdungseffekt, or alienation. I suppose it’s much more hip in our world where po-mo speak infests our language and things sound more impressive when they have a hyphen. But I’m not fundamentally interested in Ms. Drury’s word usage. I’m interested in her play.

Brief Fact Summary. The Petitioner, a man who had one eighth African blood and seven-eighths Caucasian blood (Petitioner), filed suit alleging that a statute requiring separate railway cars for whiles and colored races violated the Fourteenth Amendment of the United States Constitution (Constitution).

Synopsis of Rule of Law. The Fourteenth Amendment’s purpose was to enforce the absolute equality of races, but does not purport to abolish distinctions based on color. The Fourteenth Amendment is not violated by laws requiring the separation of the races.

German was the third language I learned after English and Norwegian, which I learned in third grade at Maple Elementary. I’ve always been fascinated by Germany and German people, and how they navigate that murky water of so-called freedom within their constraints of service and obeisance. It’s a German duty to obey. Has been since King Johann’s motto of Ich dien. Even free speech is subjugated to service. Even a smart man like Immanuel Kant could write “Only one ruler in the world says: ‘Argue as much as you please, but obey!'” and tout it as a sign of his culture’s enlightenment. In that sense they aren’t so different from Americans who believe so heavily in their own freedom, yet show the same tendency to leisurely acceptance. The only difference is that Americans make no pretense of serving others.

A black play knows all about the black hole and the great hole of history and aint afraid of going there.

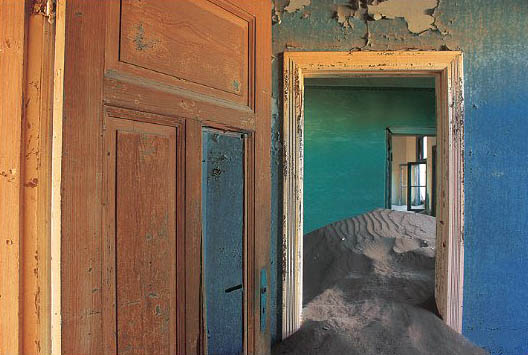

I know the story of the Herero. I still dream of the spooky pictures we made of Namaqualand in a workshop with my teacher.

But the Herero, and their genocide, and the Germans, and Southwest Africa are not what the play is about, of course. It’s about history. And, as Herb Blau was fond of reminding me, history is the thing that hurts.

Above all, I think, We Are Proud to Present a Presentation about the Herero of Namibia, Formerly Known as Southwest Africa, from the German Sudwestafrika, Between the Years 1884-1915 isn’t a play about racism or “racerelations” as Suzan-Lori Parks says it. If it were, it would be a disaster, which is why Ms. Drury has moved deliberately away from an easy representational model of drama. It’s about people trying to represent racism and struggling with how to represent it. And that’s the whole point of Brecht. In spite of the largely anti-intellectual fear among American theatrical personages, actors can think and should. Audiences can think. People do not cease to be citizens because they are acting. To answer Brecht’s question “Is it possible, perhaps, to replace the fear of fate with the thirst for knowledge, to replace pity with Hilfsbereitschaft?” the answer is obviously yes. It’s exactly what We Are Proud to Present a Presentation about the Herero of Namibia, Formerly Known as Southwest Africa, from the German Sudwestafrika, Between the Years 1884-1915 is suggesting. Discussion can be balanced just as the cast itself is balanced: three black actors, three white actors. Each of the actors can represent a particular attitude in society without necessarily indulging in personal psychology; more accurately, they can switch back and forth between psychology and sociology to accomplish whatever goals they wish. What they can’t and don’t try to do is tell the audience how to think or feel.

I wanted to free the audience and the performers of that need to make everything ok, because it’s just not ok.

One of the many reasons I don’t obsess about racism in the theater is that I have very little cause to do so. I can’t speak for black folks, even when white folks think I can. I can’t speak for white folks, even when black folks think I do. I can only speak for myself. All I know about racism is that it is violent and complex. Only an idiot thinks it doesn’t exist. Only a fool thinks it can be conquered through a power struggle. It’s the water we all swim in. What I think and what I do is always touched by it. Sure, the water’s polluted but I still have to swim.

The destinies of the two races in this country are indissolubly linked together, and the interests of both require that the common government of all shall not permit the seeds of race hate to be planted under the sanction of law. What can more certainly arouse race hate, what more certainly create and perpetuate a feeling of distrust between these races, than state enactments which, in fact, proceed on the ground that colored citizens are so inferior and degraded that they cannot be allowed to sit in public coaches occupied by white citizens. That, as all will admit, is the real meaning of such legislation as was enacted in Louisiana.

There’s too much talk about racism that is just that: talk. I’m not convinced that any part of the institution of American racism will every change through talk. What I am convinced of, however, is that people from every faction who have any interest in racism as a subject want answers and solutions, which is exactly what renders most plays about racism intolerable. Art is a very poor place to find answers. It deals in probabilities and possibilities. Certainties lie beyond its reach, at least the certainties of shared reality. Any artist who thinks she has the answer to the problem of 400 years of racism in the United States is probably a liar or a lunatic. Most certainly she is a bore. I’ve been bored by that playwright enough already. I’ve fallen asleep at so many “black plays” and “relevant plays about race” in the United States in the past decade that I’ve taken to carrying a napkin for my sleeping drool. I’m tired of the homilies, tired of the minstrelsy, the simplistic divisions, the clichés, the complete lack of respect for complexity of idea and of form. And I’m truly tired of the emphasis on catharsis. It is the opium of the theater. Brecht calls it “hypnosis” for a reason.

It’s true we desire solutions for all of our social ills. But first we need options. Art is supposed to help provide those options. Americans don’t need people telling black playwrights that formal experimentation is “white.” Americans don’t need black people telling other black people that they don’t measure up, and checking their privilege to score brownie points among the flag wavers of essentialism. We don’t need to be told, as I’ve been told by at least three different festivals for African American art that “It’s not black art if it doesn’t deal with black issues like drugs and gun violence.”

A black play doesnt have anything to do with black people. Im saying The Glass Menagerie is a black play.

SAY WHAT?

EXCUSE ME?!?!

Cause the presence of the white suggests the presence of the black. Every play that is born of the united states of america is a black play because we all exist in the shadow of slavery. All of us. The Iceman Cometh is a black play. Angels in America is a black play and Kushner knows he’s a brother. Its all black.

We’ve been hypnotizing ourselves into delusion for a long time in American theater. It’s about time more playwrights like Ms. Drury come along and snap us out of it.

All we need to do is see you SHUT UP AND BE BLACK.

Help that woman.

Help that man.

That’s what brothers are for, brother.