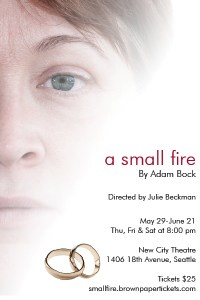

Don’t learn too much about the plot to A Small Fire. One of my companions was seeing the play again and said it was more affecting the second time. While I believe her, watching the play cold links the audience to Emily, who is taken for a strange ride, and we go on her strange ride with her.

Here’s enough: Emily Bridges (Teri Lazzara) supervises construction sites. Billy Fontaine (Ray Tagavilla) is her next-in-line and her buddy. John (Gordon Carpenter), her kind husband, is helping Jenny (Sara Coates), their daughter, with her wedding plans. Jenny intends to marry Henry, about whom Emily is unsure, and Emily has conveyed this to Jenny. Jenny relaxes with her father but feels disconnected from and uneasy with her mother.

The title refers to a small fire—a dishcloth left on a hot stove: John (Carpenter) has smelled it; Emily (Lazzara) has not. Emily is particularly dismissive of the episode—nothing burned down. Briefly John and Emily blame, deny, squabble, appear to move on. John is bothered. Emily did not smell danger. Emily has missed the foreshadowing.

Plenty of people play chameleon. But that’s not Emily Bridges’ approach. She plays things straight. Nevertheless, her work friend, Billy, finds her fun, kind, and reliable. Husband John finds her loveable if grumpy and preoccupied. Daughter Jenny finds her difficult and distant. Why can’t Jenny enjoy her mother, when Billy can? Why can’t Emily laugh with Jenny? What binds John and Emily? How does each experience the other so differently? We see and understand their different takes, but Emily remains Emily.

And then Emily changes, even to herself, and through asking what makes Emily Emily, we ask, what makes us each ourselves? We know so much of who we are through our interactions with others, and our environment. What if something forced these interactions to shift or vanish?

I thought of José Saramago’s novel Blindness, also about a baffling loss of sensory capacity and what it means mechanically and metaphorically, and how it messes with and clarifies relationships, identity, and purpose. How much of ourselves depends on how we have learned to communicate, on how we understand our surroundings? Are we still ourselves if our means shift?

The staging gives us layers. Action begins at a construction site, Emily’s workplace—hard hats, sheet plastic, building plans. We see her in charge. We move into the Bridges’ living room—comfy furniture, fireplace screen, drinks bottles. We see Emily “at rest.” Later, we move further into their home. We also get taken to the doctor’s waiting room, Billy’s rooftop, and Jenny’s wedding venue. The set feels rich—plenty of cues to location without feeling crowded in this limited space. The compactness comes across as just right. The final scene, significantly, takes place in the innermost layer.

I see much fringe theater in this town. In the last month I’ve also seen shows at West of Lenin, TOJ, The Rep, ArtsWest, Center House, and some un-named venues. I see some big house shows too. Pamela Reed bowled me over in Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? This production impressed me more than all other recent theater forays. This script is a good story with some surprises. The casting is strong and credible. The direction is intelligent. The staging is clever.

I see much fringe theater in this town. In the last month I’ve also seen shows at West of Lenin, TOJ, The Rep, ArtsWest, Center House, and some un-named venues. I see some big house shows too. Pamela Reed bowled me over in Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? This production impressed me more than all other recent theater forays. This script is a good story with some surprises. The casting is strong and credible. The direction is intelligent. The staging is clever.

Teri Lazzara grows more and more interesting to watch as the play marches on. We fall in love with the rough-edged Emily Bridges because Lazzara so fully conveys her anguish, her honesty, and her isolation. I’m convinced Carpenter is a sweet guy because of this sweet performance as John. Tagavilla charms us with his humor and solidity. We need the warmth of this character, and his indebtedness to Emily, to get the complete Emily. Coates acts as if she is in her own family and said, at the industry night after-party in the lobby, “Gordon is my dad.” This level of chemistry between the actors is a gift to the audience. Each of the actors has a plum role here. While this is Emily’s story, the intimacy of the play and the importance of each viewpoint also makes it a bit of an ensemble piece. This is a fine cast and every member turns out a sharp and memorable performance.

Director Julie Beckman saw A Small Fire at Portland Center Stage earlier this year. While she says it was good, and that the play worked, each scene, often between just two actors, seemed to be on a small island on the large stage. At New City, the audience shares the space so closely with the actors that there can be no such islands. Beckman has brought this smart cast to the perfect place. The experience is close; the performance is tight.

My only complaint was the heat of the room. Dress accordingly. A big, satisfying experience awaits you in this tiny Seattle venue.