[media-credit name=”Tyler Korth” align=”alignright” width=”403″] [/media-credit]

[/media-credit]

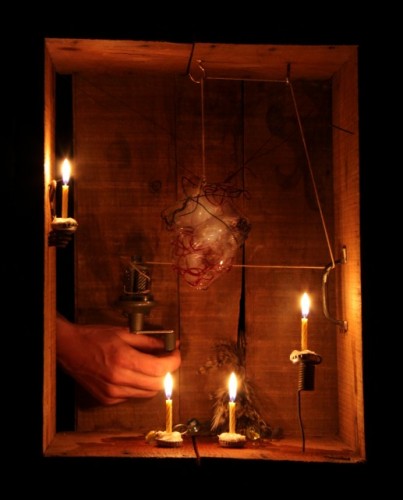

Though it be nominally a world premiere, Kyle Loven’s Loss Machine is a piece I have seen before in smaller versions over the past two years.

Contrary to what you may have read in the Seattle Times, the piece is not ninety minutes. It was on the night I saw it seventy-three minutes.

Contrary to what you might have read in On the Boards’ own press, Loss Machine has nothing to do with Rube Goldberg. Rube Goldberg’s cartoons feature incredibly complex mechanisms to do something simple, such as sharpening a pencil. They are about bureaucracy and mechanization–an American version of Kafka.

Mr. Loven’s “loss machine” is, quite simply, an apartment complex not filled with complex machines but rather filled with simple items: purses, socks, tissue paper, salt. It is not a machine in the sense of a contraption; it is a machine in the sense of a process that works itself out inevitably.

Animating simple objects and imbuing them with a very human life is Mr. Loven’s bailiwick. The process is easy to dismiss as reminiscent of something else, if one is completely insensate or a congenital idiot. While critics love comparisons, most of them irrelevant, Mr. Loven’s process is quite distinctive.

That he relies on an anti-illusionist method to accomplish his animations makes them even more remarkable. Throughout his earlier work, such as Crandal’s Bag or When You Point at the Moon, Mr. Loven has often included himself as a character who interacts with his own puppetry. Here he has taken much more of a background role, yet he does not hesitate to remind the audience visually that his hands control everything. The artist is always present. This sometimes functions as a Verfremdungseffekt, to remind the audience that this is artifice: this is magic.

It is no less effective magic for being above the table. In fact the magical effect becomes even stronger. The purpose of the Verfremdungseffekt is not to stifle emotion but to activate the rest of the mind as well, thus giving the emotion a basis for action. Here, as the magician clearly shows his tricks, the purpose is to prevent the audience from simply falling in love with effects by making the audience pay attention to their cumulative structure. Not “How’d he do that?” but rather, “What will he do next?”

This might sound very intellectual and it is: A brilliant mind is at play here. It is also wonderful, in the real sense of the word. Above all, it is deeply effective.

The entire Loss Machine as an environment comprises little objects–the detritus of life. They are banal, and it is their banality that gives them such a power to astonish. One expects extraordinary things from extraordinary objects. The power of Mr. Loven’s work is that he draws extraordinary things from ordinary objects. His work has a feeling of dark strangeness. Loss Machine is even darker than his previous work–especially the third section, “Cost”–but by playing the theme of loss with exquisite variations, it becomes a symphony of beautifully dissonant images that ultimately affirm life and connect a viewer to the hidden world not only of lost things but lost thoughts and lost feelings.

Kyle Loven’s explorations are always provocative and gorgeous. Loss Machine is especially so. In particular, the strength of the sound effects and overall lush design of electronic music matches Mr. Loven’s work more beautifully than anything in his past oeuvre, and the brilliance of his partners in sound has driven him to a high level of invention and deft execution. This is the maturing work of a future master. I await his future work with excitement.